Shortcuts in Windows

Windows shortcuts exist to make life easier. Attackers noticed.

In an effort to improve the usability of the Windows operating system, LNK files were introduced with the launch of Windows 95 [1]. The concept of a pointer to another file or directory was not unique: symbolic links were introduced in 1982 in 4.1a BSD Unix [2]. The Windows LNK file is, however, different in a number of ways: its complex binary file format [3] can point to files, directories, but also start programs with command-line arguments. Various optional metadata fields allow the operating system to find the intended target even when it has been renamed or moved; additionally, it is possible to store window settings, set the working directory the target should operate in, and a custom icon can be specified.

Although LNK files can be opened from a command prompt or script, they remain largely a GUI feature. Shortcuts can be recognised by the white square containing an arrow rendered on top of the shortcut’s icon in the bottom left corner. This visual cue is, in a way, a security feature: it makes it clear to users that upon double-clicking the file, something else will be opened. From an end-user perspective, the only practical way to inspect what an LNK file points to is by right-clicking it and clicking Properties. This opens the Properties dialog, which reveals the target of the LNK file.

Ever since their introduction, LNK files have been used by threat actors. A notable example is the Stuxnet campaign, which exploited critical Windows vulnerability CVE-2010-2568, where specially crafted LNK files could trick the system into loading arbitrary DLL files without the user even opening them [4]. More commonly, however, LNK files are used in social engineering attacks: email phishing [5], social media phishing [6], torrents/Usenet downloads [7], USB worms [8, 9] and fake downloads [10]. In all of these attacks, the shortcuts disguise themselves as something else, e.g. a PDF document, a drive folder or a legitimate piece of software, and lure the user into opening them. Upon triggering, the attacker’s payload is executed - as the aforementioned examples show, these often rely on Living off the Land Binaries and Scripts (LOLBINs/LOLBAS) [11].

Thus, the fact that LNKs still work as an attack vector, comes down to trust: users are made to believe that the shortcut opens something they are after or trust. The best defence is therefore to validate the target of an (unknown) LNK file prior to opening it.

But can Windows Explorer’s File Properties dialog be trusted?

LNK Structure

To understand LNK attacks, let’s consider how they work. Unlike symbolic links and Microsoft’s own .URL files [12], which are in plain text, LNKs use a binary file format. Microsoft provides detailed information [3] on the structure of LNK files, which tells us that LNK files have up to 5 sections, that are specified in the following order:

ShellLinkHeader, which is always present;LinkTargetIDList, which is only present if theHasLinkTargetIDListflag is set;LinkInfo, which is only present if theHasLinkInfoflag is set;StringData, which is only present if at least one of 5 specific flags are set;ExtraData, which is a generic structure of which 0 or more can be present, depending on certain flags being set.

ShellLinkHeader

ShellLinkHeader. Hover over the byte fields to see what they represent.The ShellLinkHeader has a fixed length of 76 bytes; it is the only required structure in any LNK file. It contains a number of common data fields, and defines the layout of the LNK file.

The first two fields have predefined values that the documentation warns should not be changed.

The third field LinkFlags is, albeit just 4 bytes in size, perhaps the most fundamental field: this value sets out what the remainder of the LNK file will look like. For example, setting HasTargetIdField (0x01) indicates a LinkTargetIDList will be present, HasLinkInfo (0x02) indicates LinkInfo will be present, HasArguments (0x40) indicates StringData will contain command-line arguments, and so on. The documentation defines 25 possible flags that can be set here; meaning there are 225 ≈ 33.5 million possibilities.

This flags field is followed by FileAttributes, which indicates what file attributes the target has set; these are merely hints for how Explorer should display the target. Similarly, the following CreationTime, AccessTime and WriteTime represent timestamps of the target - these can be useful forensic artifacts. Finally, some integer/enum fields are defined: FileSize, IconIndex, ShowCommand (which controls if the target should be opened minimised, maximised, or normal), HotKey, and some reserved fields.

LinkTargetIDList

c:\test\a.txt. Hover over the byte fields to see what they represent.This structure is the main mechanism to represent the target file/directory of the LNK. Although not required, it is commonly found in LNK files - for example, an LNK file generated through Windows Explorer will always specify this structure. Typically, you will find an absolute path here: it could be on the local drive, a removable drive, a network path, or any other location that can be accessed through UNC [13].

The LinkTargetIDList structure represents a path as a list of Shell Items [14], which unlike LNKs themselves, are not formally documented. Each part of a path may contain extra metadata, such as size, last modified, and optionally even NTFS attributes. This allows Windows to find targets even if they have been renamed or moved on disk. Next to this, special locations (e.g. My Computer, Network Locations, Control Panel) as well as special file types (e.g. Control Panel items) can be represented. For the purpose of this post, we will limit ourselves to normal, on-disk paths.

LinkInfo

Regarding this optional structure, the documentation states it “specifies information necessary to resolve a link target if it is not found in its original location” [3, p. 19]. To that end, it can contain both a local path and one or more network-based representations of the same target, including UNC paths and volume identifiers. By combining filesystem-specific details such as volume serial numbers with path data, this field enables more robust target resolution than a simple string path, but also exposes a rich source of forensic artefacts that can reveal original file locations, network shares, and execution environments.

StringData

COMMAND_LINE_ARGUMENTS set to --my-command-line-flag. Hover over the byte fields to see what they represent.The next section contains, as the name suggests, strings. Depending on which LinkFlags are set, up to five strings could be defined here; this includes the working directory, the LNK’s icon location, and any applicable command-line arguments.

The layout for a string captured in this section is simple: a byte sequence representing an ANSI-encoded string is provided, preceded by a two-byte field denoting the character length of the string; non-NULL terminated. This implies that strings can be up to 216 = 65,536 characters long. If the LinkFlag of IsUnicode is set, a Unicode-encoded string is expected.

ExtraData: EnvironmentVariableDataBlock

c:\hello.txt. Hover over the byte fields to see what they represent.The final section in an LNK file is the ExtraData section, which contains 0 or more ExtraDataBlock structures. The documentation [3, p. 28] defines 11 distinct subtypes, each with its own structure and rules.

For the purposes of this post, let’s look at the EnvironmentVariableDataBlock subtype, which is expected when the HasExpString flag is set. This structure has 4 fields, which all have a fixed length. The BlockSize should always be set to 0x0314 (788); followed by a static BlockSignature field (which declares that this block is an EnvironmentVariableDataBlock). After this, we see two more fields: TargetAnsi and TargetUnicode, which, as their names suggest, contain the target path with ANSI encoding (e.g. Windows-1252 [15]) and Unicode encoding (UTF-16LE [16]), respectively. Both have fixed lengths of 260 and 520 bytes, respectively. It is worth noting that this structure is always the same, regardless of whether the IsUnicode flag is set.

Explorer is forgiving, when it shouldn’t be

Variant 0: CVE-2025-9491

With this background in mind, let’s start by understanding the much-debated [17, 18] CVE-2025-9491 that has been abused in the wild for quite some time [19].

As discussed before, the LNK format can specify command-line arguments with a length of up to 65,536 characters [20]. For whatever reason, in Explorer, the Target field only displays the first 256 characters of a command-line string. As such, it is possible to “hide” command-line arguments by padding the provided command-line arguments: whitespaces for example are typically ignored by the target process [21]. This means that although the target program will receive the full, padded command-line arguments, in most cases it will ignore all whitespace and simply interpret the remainder of the command-line argument string.

The original post highlighting this [22] describes how threat actors have been observed to pad with plain spaces (\x20) or tabs (\x09). When viewing the Properties dialog of such LNKs, it immediately suggests something is off.

The same post mentions a more stealthy approach, in which line feeds (\n, i.e. \x0A) and carriage returns (\r, i.e. \x0D) are used. This works because Windows treats these characters as whitespace, and are rendered in Explorer as a single character, even when repeated many times.

This is useful, because:

- The command-line arguments are hidden.

Its effectiveness is limited by:

- The target executable is still visible. Thus, if the target does not match the presented goal, it stands out as anomalous (e.g.

invoice.pdf.lnkwith a target of%COMSPEC%is unexpected); - The process execution will still carry all whitespace characters, making it easily detectable; and,

- The technique has been used in the wild for many years. Defensive software like Windows Defender detect these out-of-the-box.

Variant 1: Trust me, I have an ExpString

Now consider this similar variant, which is lesser known despite having been documented before [23]. The LNK Format Definition states that if the HasExpString flag is specified, an EnvironmentVariableDataBlock must be provided.

When HasExpString is specified, and an EnvironmentVariableDataBlock is specified with a TargetAnsi/TargetUnicode value of just null bytes, Explorer does two unexpected things. First, it disables the target field, meaning the target field becomes read-only and cannot be selected. Secondly, it hides the command-line arguments; yet when the LNK is opened, it still passes them on.

mshta.exe code. The shortcut was created with lnk-it-up.

This is useful, because:

- The command-line arguments are hidden; and,

- The target cannot be modified.

Its effectiveness is limited by:

- The target executable is still visible. Thus, if the target does not match the presented goal, it stands out as anomalous; and,

- Targets with environment variables cannot be used, due to the flaw’s reliance on

TargetIDLists.

It is therefore similar to CVE-2025-9491’s behaviour, but has the advantage of being less easily detected due to it not having padded command lines.

Variant 2: Trust me, ““I know what I’m doing””

At this point, let’s look at a new variant that has, to my knowledge, not been documented before. The LNK File Definition shows that it is possible to specify a target in multiple places. For example, one can set the HasTargetIDList and HasExpString flags and provide the a path as in the TargetIDList structure and one in the EnvironmentVariableDataBlock structure.

Now, which does Explorer prefer when both are defined? By default, it will show the Environment Variable version. Even if you set conflicting values, e.g. if TargetIDList is set to c:\file1.exe and the EnvironmentVariableDataBlock to c:\file2.exe, the latter will take precedence: file2.exe will be shown in the Properties dialog, and will be executed when the LNK is opened. In this scenario, if c:\file2.exe does not exist, you will be told so - even if c:\file1.exe does exist. The TargetIDList version is thus completely ignored here.

However, it turns out that Explorer does something unexpected if you provide a path to the EnvironmentVariableDataBlock that does not meet Windows’ file path definition: although it shows the value of EnvironmentVariableDataBlock in the Properties dialog, upon realising the path is invalid, it falls back to the value provided in TargetIDList, which is not visible in the UI at all. This can lead to the strange situation in which Explorer will show one target in the Properties dialog, but executes a completely different one when the LNK is opened.

README.pdf, but when opened, executing Windows Calculator. The shortcut was created with lnk-it-up.

Generating an invalid Windows path does not have to be difficult: simply including one of Windows’ reserved path characters will do [24]. For example, setting EnvironmentVariableDataBlock to "c:\path2.exe" (note the double-quote characters at the start and end) will make the path appear valid, even though it is not: double quotes are not allowed in Windows paths.

This behaviour is useful, because:

- The target program/file/directory is completely spoofed.

Its effectiveness is limited by:

- If command-line arguments are present, they will be visible (unless this technique is combined with e.g. CVE-2025-9491); and,

- Targets with environment variables cannot be used, due to the flaw’s reliance on

TargetIDLists.

Variant 3: Trust me, I have a valid LinkTargetIDList

Let’s look another, previously undocumented example. There is yet another place where an LNK’s target may be documented: the LinkInfo field.

Here is when again something unexpected happens: if you specify the HasExpString flag and EnvironmentVariableDataBlock is set to any value; then also set the HasLinkTargetIDList flag and provide a non-conforming LinkTargetIDList value, the LinkInfo field is used as a fallback to identify the “real” path. Yet for unclear reasons, Explorer’s Properties window will display the EnvironmentVariableDataBlock value, despite never actually executing it.

This results in the strange situation where the user sees one path in the Target field, but upon execution, a completely other path is executed. Due to the field being disabled, it is also possible to “hide” any command-line arguments that are provided.

c:\README.txt, but when opening, executing Windows Calculator. Note that this was tested on Windows 11 23H2. The shortcut was created with lnk-it-up.

This behaviour is useful, because:

- The target program/file/directory is completely spoofed.

- Any command-line arguments can be hidden.

Its effectiveness is limited by:

- The LNK has to be executed twice; the first time the LNK will repair itself without executing anything, the second time the execution will take place.

- Targets with environment variables cannot be used, due to the flaw’s reliance on

TargetIDListandLinkInfo. - In Windows 11 24H2, this trick no longer appears to be working.

Variant 4: Trust me, I have a Unicode target

Bringing it all together, consider this final example that, despite its relative simplicity, is arguably the most powerful.

As discussed earlier, the EnvironmentVariableDataBlock has a somewhat unusual structure: regardless of whether or not the IsUnicode flag is set, the block includes a fixed-length field for both ANSI and Unicode (TargetAnsi and TargetUnicode, respectively) [25]. What happens if you only provide one of them? When you set only TargetAnsi and fill out TargetUnicode with NULL bytes, Explorer realises something is wrong and will show the LinkTargetIDList value in the Properties dialog instead. It also disables the Target field and for reasons unclear, it hides any command-line arguments provided. However, when you execute the LNK something weird happens: it still executes the ANSI value in the EnvironmentVariableDataBlock, with any command-line arguments present.

c:\your-invoice.pdf, but when opened, executing Windows PowerShell code. The shortcut was created with lnk-it-up.

Unlike the previous variant we looked at, opening the LNK executes the “actual” target immediately, not having to open it twice. Additionally, because in this case the spoofed target is in TargetIdList and the actual target in EnvironmentVariableDataBlock, the actual target may utilise environment variables.

This behaviour is useful, because:

- The target program/file/directory is completely spoofed.

- Any command-line arguments are hidden.

Its effectiveness is limited by:

- The LNK will repair itself after the first execution. However, as discussed before, this will not be a limitation if your goal is social engineering.

Prevention and detection

To some, the findings presented above may come across as full-on security vulnerabilities. Microsoft however argues that as it requires the user to do something, without breaking any security boundaries [26], it is not a security vulnerability. This is not entirely unreasonable as ultimately, most of these boil down to being UI bugs. Yet, they are UI bugs that affect the trust a user may put in a file, and can be the start of a more elaborate intrusion. Although a CVE was assigned for one of these bugs [27], Microsoft still seems hesitant to address findings like the ones presented in this post as security issues.

In lieu of these flaws being fixed, it may be worth proactively detecting them. Defensive software like EDR does often not monitor what is inside an LNK file until opened. There is an opportunity to inspect LNK files manually with specialised tools [28, 29, 30 and others], but be aware that unlike Windows Explorer, these tools are very strict: non-standard LNK files may not be parsed at all despite working without problem in Windows Explorer. Another, possibly more robust approach may therefore be to look for commonly used suspicious terms in LNK files [31]. However, this makes assumptions about flags set and/or keywords used.

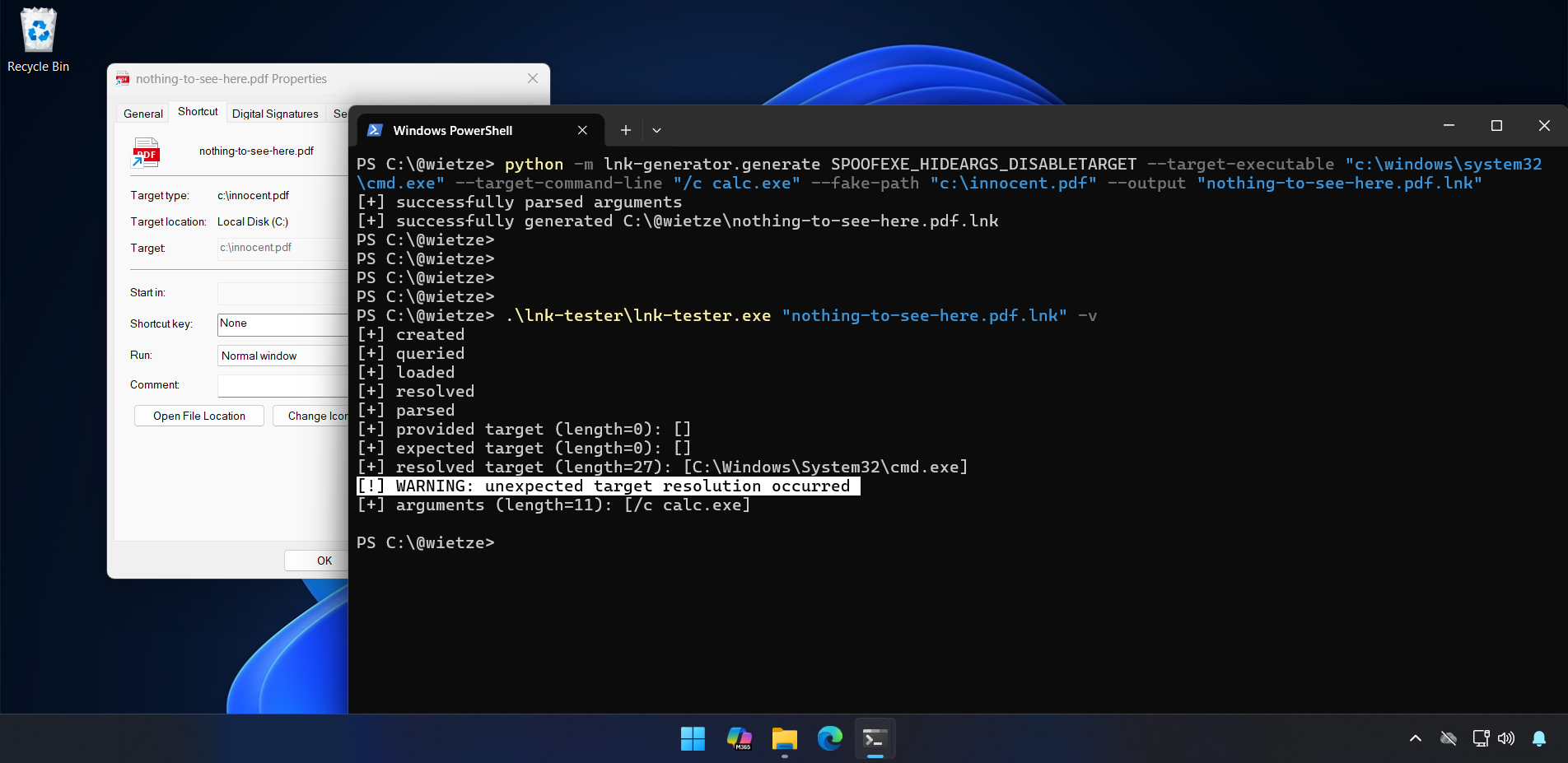

To help with both the creation and identification of the deceptive LNK files discussed in this post, the open-source project lnk-it-up [32] is now available. It contains two tools: the lnk-generator tool [33] can create LNK files taking advantage of any of the five variants discussed in this post. The lnk-tester tool [34] uses native Windows APIs to predict, for a given LNK file, what Windows Explorer will display as target and what will be executed upon opening; meaning it can identify various LNK spoofing techniques.

lnk-generator, and the resulting LNK file being tested with lnk-tester, warning that there is a mismatch between the expected target and the actual target.

In summary, we have seen that LNK files are unpredictable because crucial pieces of information might be hidden or entirely spoofed, meaning it is not straightforward to anticipate what will happen when an LNK file is opened.

Don’t trust LNK files. Even when a dolphin tells you to.